Millennium Plus or Sustainable Development Goals:How to Combine Human Development Objectives with Targets for Global Public Goods?

2014/06/25

abstract

For the last 20 years, the international development debate has been dominated by two trends that seem at first to be heading in a similar direction. However, under closer scrutiny they differ with respect to their focus and underlying philosophies. These are on the one hand the agenda of reducing poverty in developing countries in its various dimensions (lack of income, education, water, political participation, etc.) that found their expression in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). On the other hand, there is the idea of sustainability that became popular at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and that at the Rio 20 Summit in 2012 generated a parallel concept to the MDGs: the so called Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

As a result, two separate processes started within the United Nations (UN) system: one of them to discuss whether there should be a new global development agenda after the term of the MDGs ends in 2015, and what such an agenda should entail; and the other to compile a list of possible SDGs. For more than a year, there was a very real possibility that these two processes could result in two separate sets of goals guiding international development policy after 2015.

However, UN member states, which met in September 2013 in order to design a process for the negotiations on a post-MDG agenda, were luckily very aware of this risk. In response, they adopted a very short, almost vacuous declaration, which contained mainly two messages: first, that future development goals should be truly universal targets, and second, that there should be only one “single framework and set of Goals” – i.e., no separate MDGs and SDGs.

The challenge is now to design a post-2015 agenda that fulfils the aspirations of both, the proponents of a second set of MDGs as well as the proponents of SDGs. The latter see poverty as merely one of a number of global issues to be addressed, which again makes those in favour of the MDGs afraid that poverty reduction will become secondary in an SDG agenda as just one item among many others. On the other hand, the pro-SDG side criticises the MDGs for having a too narrow concept of development and giving immediate results preference over socially, economically and ecologically sustainable ones. Both are valid concerns, and thus it is important to find a solution that takes them both into account, while still satisfying the interests of countries around the world.

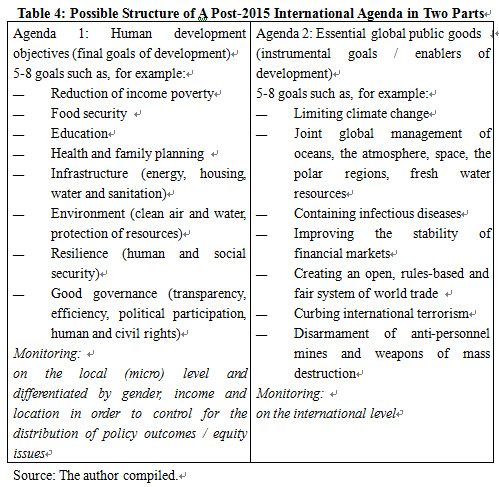

This article discusses what a solution could be. It argues that a future post-2015 agenda should be made up of two separate but mutually referring sets of goals – one concentrating on human development, the other on global public goods – because this distinction would address the most serious concerns of the proponents of either pure MDGs or pure SDGs.

The article proceeds as follows: Section 2 looks back into the past in order to recall how the MDGs emerged. Section 3 identifies their main strengths, Section 4 their weaknesses. Section 5 explains why and how the competing idea of SDGs came up. Section 6 discusses which criteria a post-2015 agenda would ideally fulfil. Section 7 discusses the key question which goals that agenda should contain. Section 8 suggests that the post-2015 agenda should have two separate but inter-related lists of goals. And Section 9 examines the scope of a post-2015 agenda

I. Emergence of the MDGs

The MDGs are the outcome of a development that entailed an at least partial departure from the so-called Washington Consensus, which dominated the international debate during the 1980s. It found expression above all in the stabilisation and structural adjustment programs of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank that provided for consolidation of the current accounts and budgets of indebted developing countries, continuous and non-interventionist monetary and fiscal policies and structural market reforms (market opening, deregulation and privatisation). Poverty reduction was largely equated with higher economic growth, the assumption being that such growth would, sooner or later, benefit the poor through trickle-down effects.

In the early 1990s, however, it gradually became apparent that this assumption was, at least in its then current form, not tenable. Indeed, in many developing countries – above all in Africa, but also in Latin America – poverty had even worsened under the SAPs.[①] As early as the mid-1980s UNICEF, the UN Children’s Fund, voiced criticism of the high costs exacted by the SAPs and called for “adjustment programs with a human countenance.” This demand was underpinned programmatically by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which, in 1990, released its first Human Development Report (HDR), a counter piece to the World Bank’s World Development Report. The HDR argued that economic growth did by no means automatically come along with social development (e.g. on education and health indicators).[②] The report further noted critically that the development debate was largely dominated by a one-dimensional, purely economic understanding of poverty. Based on the capabilities approach pioneered mainly by Amartya Sen[③], poverty was now defined as multiple deprivation of capabilities, i.e. as a lack of means that are needed to carry out the activities one cherishes and to live a life of self-determination.[④] Five groups of capabilities can be distinguished:

economic capabilities (on the basis of income and assets),

human capabilities (health, education and access to food, water and habitation),

political capabilities (freedom, voice, influence, power),

socio-cultural capabilities (status, dignity, belongingness, cultural identity) and

protective capabilities (protection against risks).

The disappointing balance of development in the 1980s also led to the calling, in the early 1990s, of a number of international conferences in the UN framework that dealt with various aspects of social and ecological development. The first of these conferences was the 1990 Summit on Education for All in Jomtien (Thailand), which was organised by UNESCO; at it the international community defined a number of educational goals, including an important one calling for access, for all children – girls and boys alike – by the year 2000, to a complete course of primary education. It was followed by the World Summit for Children in 1990 in New York. One conference of particular importance for what was to come was the 1995 Copenhagen World Summit for Social Development. And each conference adopted long lists of goals in its respective topic (education, food, child development...).

In 1996, the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD/DAC) released a report on “Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation”, which took up the central goals defined by the main world conferences and proposed a global development partnership geared to achieving these “ambitious but realisable goals”[⑤] by the year 2015. These so-called International Development Goals were to be pursued and implemented by each country on its own. The key consideration here was to make donor aid more effective and poverty-oriented. In addition, the OECD/DAC started taking poverty as a multi-dimensional phenomenon rather than simply a lack of income.

Almost all of the International Development Goals were taken up by Chapter 3 of the Millennium Declaration, which was adopted by the United Nations (UN) at its Millennium Summit in 2000. Other main chapters of the Millennium Declaration are about Peace, security and disarmament (Chapter 2), Protecting our common environment (Chapter 4) and Human rights, democracy and good governance (Chapter 5).

And one year later again, a commission was constituted with representatives from the UN, the World Bank, the OECD and other international organisations to bring the goals of Chapter 3 into a new form and specify them by 16 targets and 48 indicators: The MDGs were born, which were subsequently extended to 21 targets and 60 indicators today.

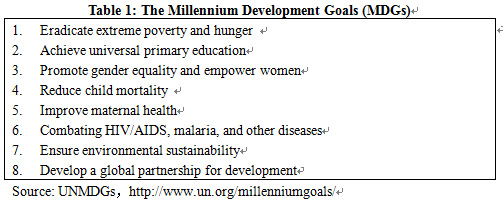

The time had come, eleven years after the end of the cold war and before the emergence of possible new international conflicts, and so it was possible to define clear value targets and a target year to a number of the goals in the Millennium Declaration and present them to the UN General Assembly as the MDGs in 2001 (see Table 1).

II. Strengths of the MDGs

The MDGs have four major strengths:

The MDGs are highly relevant in both objective and subjective terms. On the one hand, they measure key aspects of human well-being and human development. On the other hand, they are plausible, acceptable and easy to agree on by everybody because they are close to the imaginative capacities of everybody – if rich or poor.

The MDGs constitute a short (!) list of simple goals. Hence, they are easy to understand, easy to remember and easy to communicate.

The MDGs are goals for people. They are final end goals of development (i.e. what people want to achieve) rather than instruments (what people need only to achieve their aims). Or put differently: The MDGs measure outcomes rather than inputs.

And the MDGs are SMART goals: Specific, Measurable, Agreed upon, Realistic and Time-bound. Hence, they are suitable for measuring progress and comparing the efficiency of countries, inputs or strategies.

These strengths provide the MDGs with considerable opportunities:

Create synergies: The fact that the MDGs are a compact list of relevant goals that all relevant actors have agreed upon (at least all actors who have been relevant at the time when the MDGs were issued bore the opportunity to foster co-operation. The MDGs provided, for the first time ever, a common goal system for all actors that were active in development policy at that time, one that had been agreed on by developing countries, traditional donor countries and international organisations and was thus well suited as the basis of a global partnership for development. All actors involved were from that day on able to key their efforts and contributions to this goal system and in this way to improve (i) donor alignment, (ii) the harmonisation of bi- and multilateral donors and (iii) coherence of donor policies. This not only made it possible to concentrate forces, it also set the stage for greater continuity in international development policy.

Strengthen outcome orientation: Furthermore, the MDGs provided an opportunity for a more pronounced outcome orientation. Their very existence called for concrete achievements at a fix point in time and, hence, for (i) timely, impact-oriented inputs, (ii) aid efficiency, (iii) continuous monitoring and (iv) early readjustments. What individual donors contributed individually did not matter any more; the crucial factor was what impacts they had achieved by working together.

At the same time, there is no navigator for the MDGs: They contain just targets, no strategy of how to achieve these targets. Some people see this lack as a considerable flaw of the MDGs and therefore called repeatedly for an implementation plan. However, the lack is also a chance because it allows each developing country to pursue its favourite development path towards the MDGs. In fact, one of the core aims of creating the MDG agenda was to strengthen their ownership in development policy making: i.e. let them sit on the driver’s seat rather than to teach them once again what they should do like in the 1980s. And probably, a one-size-fits-all-strategy for the achievement of the MDGs does not even exist – until today.

Make all involved parties accountable: The existence of the MDGs invited the public both in developing and developed countries to ask governments what they were doing to achieve the MDGs, to compare the results of government policies with a benchmark and to make governments responsible for failures in the achievement of the MDGs.

Mobilise energies and resources: The fact that the MDGs are easy to accept, understand, remember and communicate makes them a perfect publicity instrument. They were very good after 2000 for redirecting public attention in the global North to the problems of the global South, for mobilising civil societies in all countries and for making them request their governments to double their efforts and contributions for international development. This made it possible to re-kindle the interest in development issues in the countries of the North and strengthen willingness to put more resources into aid. Further, the MDGs have increased the accountability of actors in both the North and the South, which contributed to greater results orientation and effectiveness of development policy and conventional development co-operation.

Proponents of the MDGs argue that, to be as successful, a new international agenda beyond 2015 should also be straightforward and realistic.

III. Weaknesses of the MDGs

Meanwhile, the critics of the MDGs point out that these have a number of weaknesses as well:

First, the MDGs constitute an incomplete agenda. They originated in the Millennium Declaration (see above), but only cover Chapter 3 (Development and poverty eradication) in addition to parts of Chapter 4 (Protecting our common environment), completely leaving out Chapter 2 (Peace, security and disarmament) as well as Chapter 5 (Human rights, democracy and good governance).

Equally, they cover only some dimensions of multi-dimensional poverty. MDG1 measures economic capabilities, while MDGs 2-7 cover human capabilities. But none of the MDGs appraises changes in socio-cultural or political capabilities (freedom, voice, access to justice, transparency), and protective capabilities are considered only at the margin.

And the MDGs leave out many of the goals that the world community had already agreed upon at the global conferences that have taken place during the 1990s. Table 2 shows that the MDGs echo, for example, only a few small segments of the six goals for education for all that the United Nations have adopted with the Dakar Framework for Action adopted at the World Education Forum in Dakar in April 2000.

Second, the MDGs neglect distributive issues. Inequality is a severe obstacle for many aspects of development. Nevertheless, the MDG agenda contains only one indicator (under the head of MDG1) capturing one aspect of distribution: the share of the poorest quintile in consumption. In addition, MDG1 focuses at least on the most deprived individuals in society. In contrast, MDGs 4 and 5 for example call for improvements in mean values of mortality rates thereby ignoring who benefits from such progress. As a consequence, many governments may be tempted to reduce child and maternal mortality rates for social groups that enjoy already below-average rates (such as e.g. the urban middle class). Progress for these groups may be cheaper and easier to achieve than for the most deprived groups who live in squatter and rural settlements and are thus more difficult to reach by health care services.

Third, some MDGs measure outputs or inputs rather than outcomes or impacts of development. MDG2, for example measures only the intake of education, regardless of its quality or relevance for economic, social and political life. Its existence has led to a significant acceleration in the rise of school enrolment rates – but in many countries at the expense of the quality of education: more children went to school but the number of teachers and the space in school buildings did not increase correspondingly.

Fourth, some MDGs cannot even be measured – either because no indicators or targets were set, or because for certain indicators no data is available. There are, for example, no reliable data for maternal mortality for the majority of developing countries for the base year 1990 that would be needed for tracking progress since then and benchmarking it against the goal to reduce maternal mortality by three quarters between 1990 and 2015. No indicators exist at all for MDG1b (productive employment and decent work for all) and MDG 7a (environmental sustainability) as well as for most targets of MDG8 (global partnership of development), which was initially meant to quantify the contribution of donor countries.

Fifth, the MDGs cannot easily be transformed into national objectives. They were originally formulated as global goals, but, without modification they were increasingly seen as national objectives in order to create national accountability.

This interpretation constitutes a particular challenge to the least developed countries, which tend to have started out in the baseline year 1990 with much poorer performance than other countries with regards to most MDG indicators. Therefore, it has been especially hard for them, for instance, to achieve MDG1c, which calls for a reduction in the share of malnourished people by half between 1990 and 2015. Countries that start from a higher share of people with malnutrition have more difficulties in achieving the goal than other countries, because the goal implies a much greater reduction for them in the absolute number of people with hunger. It would therefore be good to create a fairer formula for allocating the responsibilities or contributions to implementing the common global goals to each country.

At the same time, the seeming failure of many developing countries – most of them particularly poor and hence receiving especially large amounts of aid – was a strong factor for undermining the acceptability of development co-operation in the donor countries. We observe that on average countries with high initial levels of deprivation (high mortality rates, high non-enrolment rates) have made much more progress in absolute terms (e.g. reduction in child mortality in percentage points) than more advanced countries but that they have achieved less progress in relative terms. This is due to the fact that the trajectory of achieving the MDGs over time tends to be an S-shaped curve with little initial progress, accelerated progress in the mid-term and again little progress on the final stretch. Formulating the MDGs in relative terms comes closer to what one could expect from individual countries than formulating them in absolute terms. The most realistic formulation for MDGs applied to the national level would have been somewhere in between.

Sixth, some goals at the global level were unrealistic right from the start (e.g. MDG 2, which demands total enrolment in primary education worldwide), while others demonstrate low ambitions, at least at the global level (e.g. MDG1, which asks for halving the share of people that suffer from income poverty and which according to the World Bank has already been achieved).

Seventh, the MDGs lacked legitimacy at least at the beginning: They were selected and formulated by a committee of experts from the OECD and international organisations with hardly any representation of countries in the Global South. After that, they have not even been formally adopted by any legitimate international body: They were presented to the UN General Assembly in 2001 but without any act of formal endorsement. In a way, this procedural error has been cured later by the fact that several international declarations – which have been adopted by all UN member countries – make ample reference to the MDGs and thereby indirectly legitimised the goals. This includes, among others, the Consensus on Finance for Development adopted in Monterrey in 2002, the Declaration of the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg in 2005 and the Outcome Document of the Millennium 5 Summit held in New York in 2005. In addition, there is no doubt that the MDGs as such mirror very well some of the core concerns and wishes of poor and vulnerable people in low and middle income countries. But there is still an argument left that the MDGs go back to an initiative that originates predominantly within the OECD and which builds considerably on the traditional system of development co-operation between OECD donor countries and low-income partner countries in Africa, Asia or Latin America.

At the same time, the philosophy of the MDGs agenda is still very much coined by the world order of the cold war and immediate post cold war periods: the existence of a large number of more or less underdeveloped countries with a lack of financial and technical means and a limited number of rich countries, which were supposed to provide some kind of aid to the others. The message of the MDGs was that developing countries were responsible themselves for reaching MDG 1-7 but that donor countries had to provide support to their efforts in addition to implementing MDG8. Of course, the world today is no longer bipolar in this way; it has many very different kinds of countries with different kinds of problems including quite several ones that receive and give development assistance at the same time.

Furthermore, many criticise the MDGs as well for being too focused on the social sectors and neglecting the production sectors and economic development. This judgement, however, is unfair for two reasons: First, the MDGs do not focus on particular sectors, but on goals of human development. Achieving the health goals (MDGs 4-6) may well require investments in healthcare, but it may also (and often even more) call for investments in the education or water sector. Second, economic growth, transport infrastructure and a functioning private sector tend to be essential to be preconditions for long-term poverty reduction and for the achievement of the MDGs. But they are no ends in themselves and should therefore not have a place in an MDG agenda.

IV. Emergence of the SDGs

Proponents of an SDG agenda further criticise three other aspects of the MDGs: (i) they are not global goals and ultimately put obligations on the developing countries only; (ii) they are generally short to medium term and thus run counter to policies that are oriented towards sustainability, which necessarily have to be inherently longer-term; (iii) central areas of sustainable policies – chiefly environmental objectives – are not reflected sufficiently.

These points of criticism are justified. The first one can be addressed by the introduction of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR), which means that the formulation of the goals must take differences between countries with regards to their level of development into account. This means that every country should be requested to make progress towards all goals nationally at the national level – depending on its individual capabilities and needs – but also contribute to the achievement of the goals in other countries respectively on the international level – again depending on the each country’s individual capabilities. Such an approach would at the same time come up to the fact that the world is no more bipolar (consisting of just some donor and many recipients countries of development aid). Each country would be treated as being a potential donor and a potential recipient country at the same time.

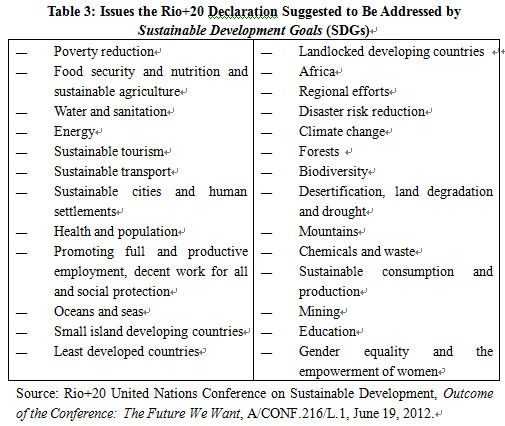

The other two points of criticism question the MDGs much more fundamentally. However, current proposals for a future SDG agenda so far have not created an alternative to the second criticism. It too envisions a rather short-term horizon and the indicators suggested so far do not include aspects of sustainability as well. The proposed agenda differs from the MDGs mostly in that there is a wider range of goals that matter from a sustainability perspective. Since each of the proposals for a possible future SDG agenda are still at the suggestion stage and sometimes vary widely, Table 3 lists the issues suggested by the Rio 20 summit’s final report for a future SDG agenda.

Of course, the MDGs are not a purely socio-political agenda and neither would potential SDGs be just environmental. Both approaches involve similar ideas. They differ mostly with respect to their underlying thinking: While the MDGs are mostly inspired by improving the living conditions of the poorest people, the SDGs main concern is shaping development sustainably.

V. Consequences for A New International Agenda

What needs to be avoided is that MDGs and SDGs are created without being coordinated. Indeed, it is necessary to design an integrated agenda for post-2015 that takes the poverty as well as sustainability debates into account.

The coexistence of two separate agendas would bear the risk that one of them would attract considerably more attention and, thus, impetus than the other or that different kinds of countries highlight one or the other. In addition, the links between both would probably be widely disregarded. So far, very little research has focused on these links – which are mainly effects of social achievements on environmental goals and vice versa. This relationship may benefit from synergies but also suffer from trade-offs... we cannot say in general.[⑥] Even trade-offs are no reason to have separate agendas. They exist anyway – no matter how we frame the future development agenda. On the contrary, the world community should even make sure that such trade-offs are taken into consideration – just like synergies. If there are synergies, these should be exploited. And if there are trade-offs, we should not close our eyes but be aware of them and try to find smart solutions to cope with them. That means that both, synergies and trade-offs would have implications on how the future goals should be formulated. And these are much easier to consider when all goals are part of the same agenda.

And this joint agenda should have the strengths of the MDGs while avoiding their weaknesses, i.e., its goals should

be highly relevant in both, objective and subjective terms like the MDGs,

have once again only a limited number of easy-to-understand goals,

be goals for people like the MDGs, i.e., final end goals rather than instruments,

be SMART (specific, measurable, agreed, realistic, time-limited),

be more comprehensive than the MDGs (include additional dimensions of development / well-being such as e.g. political, socio-cultural and protective capabilities),

consider distributional issues,

avoid inconsistencies (all targets should focus on outcomes rather than inputs or outputs),

be truly universal i.e., defined on the global level but relevant and applicable nationally for all countries,

be still binding for all countries,

be ambitious but realistic and fair – globally and for every single country

control for the sustainability of development and

be negotiated from the beginning by all countries and actors (state, society, private sector, etc.) and be formally adopted by the United Nations.

Without any doubt, very wide-ranging consensus exists today that any future international development agenda must comply with these criteria. However, there is considerable tension: Several of these criteria conflict with others:

For example, the aim to have a short, memorable list of goals conflicts with the aim to have a more comprehensive list of goals.

Likewise, it is impossible to construct a comprehensive agenda covering all relevant aspects of development/well-being with only SMART goals. Some aspects of development/well-being are difficult, others are impossible to specify and quantify. For example, there is a reasonable explanation for the fact that Chapters 2 and 5 of the Millennium Declaration (Peace, security and disarmament; Human rights, democracy and good governance) have been entirely neglected when the MDGs were extracted from the Millennium Declaration. It is extremely difficult to find good single proxy indicators for measuring and monitoring development in peace or human rights; probably one would need long lists of indicators (if an agreement on a canon of lists can ever be made).

Further, it is impossible for a future agenda to meet all of the following four criteria at a time: (i) to be truly universal (i.e. to be defined on the global level but relevant and applicable nationally for all countries), (ii) to be ambitious but realistic and fair – globally and nationally, (iii) to be binding for all countries, and (iv) to be still a short list of goals that are easy to understand and remember.

It is possible to fulfil two or three of these criteria but not all at a time: If goals are meant to be universal (applicable and intended to guide action in all countries) while also binding at the national level, they must be automatically convertible into national goals. The MDGs tend to be converted into national goals without adaptation to the needs and capabilities of different countries: all countries are expected to make the same progress in the improvement of MDG indicators in relative terms (e.g., to halve their respective share of people in absolute poverty). As we have argued, this practice is unfair to less developed countries because one and the same improvement in relative terms means much faster progress in absolute terms for countries that start from higher poverty levels. And it becomes even more unfair when goals are set for all countries: not only low and middle income but also high income countries.

The problem can be solved by a discrete conversion procedure, which defines different groups of countries (e.g., low, middle and high income) and assigns tasks with different levels of difficulty to each of them. It reduces only somewhat the initial problem because still countries with very different income levels must achieve the same improvement in MDG indicators as long as they belong to the same group of countries (e.g. middle income countries with a per capita annual income anywhere between US$1,036 and US$12,615 in PPPs). In addition, the procedure creates an additional problem: discontinuities at the thresholds between country groupings. These imply that a country that moves up from an income of 12615 to US$12,616 per capita and year in PPPs has to fulfil a significantly more difficult task from one moment to the next. Only continuous conversion factors can solve the problem because they make the difficulty of tasks rise smoothly and without any rupture with increasing levels of income or other parameters of development.

A continuous conversion procedure, however, is very difficult to understand – at least for non-experts – and may deliver entirely unexpected results. It would therefore offend against the fourth criterion mentioned above and hence cost the future development agenda one of the main strengths of the MDGs: that they are easy to understand, easy to memorise and easy to communicate.

Another challenge is to control for the sustainability of development. Of course, it is possible to strengthen the sustainability goal (now MDG7) to include additional aspects of environmental and natural resource protection. But the word “sustainability” has a much broader aim. It can be defined as the capacity to endure, which may be challenged not only by environmental but also by economic and social degradation. To control for sustainability therefore means that longer term negative effects of the achievement of one goal on the same or other goals are taken into account. This task calls for the definition of future international development goals as a dynamic optimisation problem, which makes these goals once again very complex and difficult to understand.

One way to solve the problem is to define target variables with side condition such e.g. the goal to reduce income poverty as fast as possible without accelerating climate change. This solution, however, creates a new problem: Poverty reduction can be measured at the global, national or sub-national level while climate change can only be measured globally. This is due to the fact that poverty reduction is a final end goal of human development – a goal for people – while climate stability is a goal for the planet. Manhood might not have to bother about it if climate change was not expected to fire back on human development after one or more decades. In this way, climate stability can be seen as a control variable for the sustainability of achievements made towards human development or as an instrumental variable for the long-term progress towards most different aspects of human development.

It is thus most important to include climate change as a goal in the future global development agenda! But it is also problematic to add it as just another goal next to final end goals of human development such as income poverty reduction, nutrition, education and health. To limit climate change is perhaps much more urgent than to take more action towards the existing MDGs but the goal is distinct from most of the MDGs in terms of the level of aggregation (global versus individual or national), time-horizon (long-term versus short-term) and function (instrumental versus final goal).

One could argue in a similar way for several other, highly important goals such as (i) the stability of financial markets, (ii) the existence of an open, rules-based and fair world trade system, (iii) the contention of infectious diseases, (iv) the joint global management of oceans, the atmosphere, space, the polar regions, fresh water resources or (v) the curbing of international terrorism. All of these are highly important global goals but mainly as instruments to control for (‘enablers of’) sustainable, long-term human development.

Finally, there is also, of course a tension between the claim that the future should be evenly agreed upon by all countries and different actors of development (states, the private sector, societal initiatives and international organisations) and the need to have ambitious goals covering all relevant fields of human development. The interests of countries and actors of development are much more diverse today than at the time when the MDGs were established so that some compromises have to be made by all parties involved. Nobody should aspire to get a perfect agenda after 2015.

Nevertheless, there is some hope for the possibility of smart compromises because in many areas, conflicts are not really due to contradictory interests in development outcomes as such. Rather, they can be attributed mainly to the fact that different countries and actors of development have different opinions on the question what a fair sharing of the costs of achieving a specific goal would be. In such a situation, the negotiations would have to focus on the distribution of financial burdens rather than the exact contents of a goal.

VI. Selection of Goals

A major issue in the negotiations on a future development agenda, which are going to start in early 2014, is the question which goals should be included in the agenda. The discussion on this issue should be guided by the selection criteria listed in the previous section – despite all problems discussed to reconcile them.

In any case, it is almost beyond any dispute that the reduction of income poverty, food security, education, health, family planning and gender equality will show up again in one way or the other (of course the focus will have to be much more on outcomes than in today’s MDGs – in particular in education). In addition, it is a good idea, and has the agreement of most countries, to include a goal infrastructure, which will encompass the already included sub-goals water and sanitation, as well as adequate housing and energy supply.

Further, there will possibly be agreement on a goal resilience that will refer to human and social security – i.e., the protective capabilities of human beings against social risks, economic risks, natural and ecological risks (earth-quakes, floods, torments, drought...), man-made ecological disasters (river pollution, soil degradation, deforestation, nuclear disasters...) and social and political risks (theft, domestic violence, violent attack, kidnapping, rioting, resettlement, torture, war, coup d’état...).

In spite of possible opposition from certain countries, it would also be desirable to introduce a framework for political and socio-cultural capabilities (human rights, good governance, peace, security, civil rights, social inclusion, etc.).

It would further be desirable to take distributive issues into consideration. This does not mean introducing an additional goal distribution but rather measuring achievements towards each goal separately for different population groups or even better giving results different weight according to the segment of the population (rich and poor, women and men, urban and rural, disadvantaged and privileged, etc.), to avoid general advances in a country for a given indicator either hiding strong internal differentiation, or in extremis overall improvements solely being the result of progress among those already privileged.

Most controversial is what can be done to improve the status of environmental goals. The Rio 20 Declaration suggests a number of objectives for a prospective SDG agenda. Many are already included in the MDG agenda – as sub-goals or indicators (i.e., biodiversity, protection of forests, reducing carbon emissions), but their commitment and status could be strengthened. Other goals suggested by the Rio 20 agenda also involve outcomes and thus could easily be included in a new development agenda (such as protection from desertification, soil degradation or over-exploitation of fresh water resources), while the same could be more difficult for goals that cannot be measured according to indicators at the micro-level and which strictly speaking are not actually final goals, but instruments, i.e. “enablers” of development such as e.g., climate stability (see Sections 5 and 6). Without them, many final end goals of development cannot be achieved on the long-term.

In the same way, it does not make much sense to add goals such as economic growth, access to technologies and drugs, fair global trade or the stability of capital markets to current MDGs. Some commentators have advocated integrating these into a future international development agenda – but they are conditions for short-term and in particular for long-term progress towards many of the final end goals of human well-being. Just like climate stability and some other aspects of environmental protection, these goals are crucial instruments rather than ends of development.

In addition, in contrast to most of the MDGs, these instrumental goals require international co-ordination. It cannot be left to the individual decisions of national governments whether these goals are achieved or not because these decisions have external effects on other countries. Free-riding is likely because the costs of measures taken to achieve these goals have to be borne individually while the benefits are shared.

VII. A Two-Part Agenda

A post-2015 agenda will therefore have to be accompanied by a second agenda of goals referring to the conservation / production of global public goods (see Table 4). This second agenda would contain many of the targets now included in MDG 8 but

also some of the instrumental goals coming from the Rio 20 process (known as SDGs). In ay case, the goals of this agenda must be more ambitious, concrete, measurable and binding than today’s MDG8. One way to think about this is to apply the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”.

Possible issues for the second agenda are: (i) climate stability, (ii) the protection of oceans against overfishing, acidification and filling with solid waste, (iii) the joint management of scarce mineral resources, global energy reserves and fish reserves, (iv) the joint management of global food production, (v) cross-border management of water reserves, (vi) the control of infectious diseases, (vii) the development of an accessible, equitable and rule-based international trading system (already a target in MDG8), (viii) stability and integrity of the global financial system, (ix) the containment of international terrorism, (x) the elimination of anti-person mines and weapons of mass destruction, etc.

In addition, the second agenda should contain an agreement on a fair distribution of the costs of actions taken for the conversation / production of these global public goods including binding commitments on development assistance for the achievement of the goals in the first agenda and on goals for policy coherence for development.

The two agendas would depend on each other and therefore form one unit. They should thus be negotiated as a package. Nevertheless, there are reasons for having separate lists:

First, the goals in the second list differ in conceptual and methodological terms from those in the first list: (i) They are instrumental rather than final goals of development. (ii) They focus on inputs and outputs rather than impacts or outcomes such as the goals in the first list. (iii) They are measured by macro-level indicators, i.e. they refer to regions, countries or the whole world, while most of the indicators in the first list are (aggregated) micro-level variables using data on individuals. (iv) They refer to global public goods, which matter for everybody on Earth, while the goals in the first list focus on the main problems of the most deprived human beings globally.[⑦]

Second, the goals in the second agenda are instrumental for those in the first agenda. The goals in the first list are also mutually supportive (like education and health) but the positive causal relation between the two agendas tends to go much more in one direction only: Poverty reduction can also have an impact on the goals of the second agenda but this effect is negative (like for example on climate change) or much weaker than the reverse impact (a reduction in the number of poor people may have a limited positive impact on the stability of the financial markets).

Third, the goals in both agendas are the expression of slightly different philosophies that are difficult to unify/bring together at equal weight in a single agenda. Adherents of the MDGs warn that their replacement by a more comprehensive SDG agenda might marginalise the issue of poverty eradication and development within a much broader agenda of solving global problems, while the protagonists of a new SDG agenda fear that introducing just a few selected goals from the outcome document of the Rio 20 summit might soak the entire sustainable development philosophy.

The separation between two lists within one package could thus also be seen as a compromise between two extreme positions: (i) of those who argue that a new international development agenda should continue to have its focus on global poverty rather than to cover somehow all global problems and (ii) of those who argue that given the interdependencies between these problems the new agenda has to be much more comprehensive than the current MDGs and that it should be radically more global rather than to focus on decreasing number of aid-dependent countries.

VIII. Scope of the Future Agenda

All goals of the post-2015 agenda should be universal in every sense of the word: The goals of the second part are so by definition, according to their preferences refer to global public goods and can thus only be measured globally. But those of the first part should also apply to all nations, bind all nations and be ambitious for all nations, rather than just developing countries, as is the case with the current MDGs. This will require differentiation to transform the global goals into national objectives, making them both achievable but also ambitious according to each country’s capacities. This will encourage the reduction of poverty, mortality and school dropout rates in the rich countries as well.

The goals should thus be seen as a global challenge that all countries can only master when they co-operate. All have immediate responsibility for the achievement of the goals in the first list in themselves, shared responsibility for the goals in the second list and intermediate responsibility for the achievement of the goals in the first list in other countries. The latter, intermediate responsibility is maintained in two ways: (i) by contributions made towards the achievement of the goals in the second list (referring to the conservation / production of global public goods, which are all essential for the achievement of the goals in the first list), and (ii) financial and technical assistance provided to the countries that are unable to achieve the goals in the first list on their own (especially very poor or fragile countries).

Aid will thus continue to be an important element in the implementation of the new development agenda, which means that aid effectiveness will still be relevant. However, financial aid at least will only matter for a smaller and smaller number of least-developed countries. At the same time, domestic sources of funding will gain importance for all countries world-wide.

An alternative to the notion of “aid” could be “financial contributions towards the achievement of the new MDGs”, which would allow a more comprehensive understanding of global development finance. The financial contributions paid by individual countries for the conservation / production of global public goods would be differentiated according to their respective wealth and per-capita income level recognizing the issue of international as well as domestic inequality and thereby allowing even for negative contributions (i.e., net receipts) for very poor countries.

This would entail a degree of automatism as well as fundamental international agreements with regard to financing mechanisms (international taxes and fees; agreements regarding illicit financial flows) as opposed to the post-colonial donor-recipient “aid”-relationship with its inherent imbalance of power and its flawed accountability mechanisms.

Ultimately, the concept of aid effectiveness would be substituted by a concept of “effectiveness of financing sustainable global development” comprising public and private, domestic and international sources of finance.

A truly universal agenda of this kind is also much better able to generate real policy coherence than today’s MDGs. So far, policy coherence has been geared towards doing ‘no harm’ to the poverty reduction objective. The new global framework, in contrast, should enable development ministries and agencies to closely co-ordinate and align their approaches with other sector ministries and agencies and to agree on a coherent strategy including common objectives and guiding principles. What is needed is a systematic and coherent conceptual approach to global development followed and implemented by the ‘whole-of-government’. Other sector ministries in member states need to do more than ensuring that their policies 'do no harm' to the poverty reduction objective. They should play an active role in the implementation of policies that serve the identified global goals and should co-operate more closely when drafting strategies in order to ensure coherence across ministries.

Policy coherence of this kind enhances donor credibility. Policy coherence and donor credibility are ultimately more important than the mobilisation of additional aid and non-aid resources.

Still, policy coherence is also not a purpose in itself. It is an essential prerequisite for development and might thus be referred to in the second list of goals of a new development agenda. But it is not a final end goal of development and should therefore not be part of the first list of goals.

[①] J. Betz, “Die Qualität öffentlicher Institutionen und die sozioökonomische Entwicklung,” Nord-Süd aktuell, Vol. 17, No. 3 (2003), p. 456.

[②] UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Human Development Report 2000, New York, UNDP, 2000.

[③] A. Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

[④] M. Lipton and M. Ravallion, “Poverty and Policy,” in H. Chenery and T. Srinivasan eds., Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 3B, Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1995, pp. 2551-2657.

[⑤] OECD/DAC ed., Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation, Paris: OECD/DAC, 1996, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/23/35/2508761.pdf, p. 2.

[⑥] M. Loewe et al., “Post 2015: Green and Social – How to Manage Synergies and Trade-offs in the Coming International Development Agenda?” Briefing Paper, Bonn: DIE, 2014 (forthcoming ).

[⑦] See H. Janus and N. Keijzer, “Post 2015: How to Design Goals for (Inter)National Action?” Briefing Paper, No. 23/2013, Bonn: DIE, 2013.